Reactor is a Java open source library for running non-blocking and asynchronous operation. Instead of allocating new threads for each task and wait idly for a response, the reactor follows the strategy of dealing with multiple operations by switching the tasks as the application needs. At first we can’t see the benefits for that, but for an application that handles many operations, this can be performance saving.

Why reactive programming?

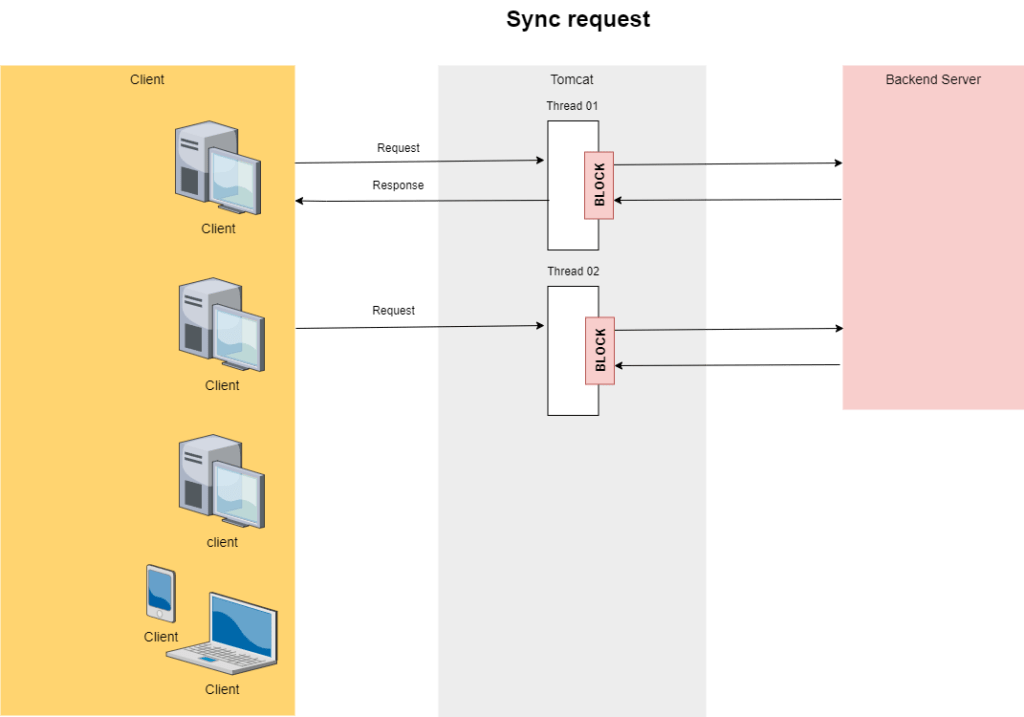

To understand why we should consider using this paradigm, we need to dive into the common problem of managing a standard java web application nowadays. First of all, how does a standard java web communicate? If you remember, the process is related to a client making a request to a server.

The server’s role is to receive the request and send back an answer to the client. To achieve this, a new thread is allocated from the thread pool by the server just to attend to this request, while the server will also be in charge of continuing to respond to further requests. So far so good. But the problem is that every time the server attends to a request, a new thread is being allocated and blocked until the final response. In other words, that is a waste of resources and if the application has a request spike, it might not hold it and it can eventually crash. We need a way to continue serving content to our clients without wasting so many resources.

How does it works?

In the reactive programming, we have the concept of publishers and subscribers. When data is available, it gets published to a designated data stream, where it remains untouched until a Subscriber consumes from it. There is no limit to the number of consumers that can access the data stream. However, the way the data is shared among the consumers can vary significantly. It is important to notice that who checks for new data is always the subscriber and not the publisher!

It is important to notice that project reactor is not limited only to Java. It has support to C# .NET, Javascript, Kotlin and also offer support to messaging systems such as Appache Kafka and RabbitMQ.

Dependency

To include project reactor to your java application, add the following dependencies into your pom.xml (maven)

<dependency>

<groupId>io.projectreactor</groupId>

<artifactId>reactor-core</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>io.projectreactor</groupId>

<artifactId>reactor-test</artifactId>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

Publisher Types

Reactor has two types of publishers that come into play.

- Mono emits 0 to 1 elements.

- Flux emits from 0 to N elements.

public interface Publisher<T> {

void subscribe(Subscriber<? super T> var1);

}

Creating Mono

Mono<Integer> m1 = Mono.empty(); // Create a empty mono

Mono<Integer> m2 = Mono.just(1); // Create a mono with number 1 on it.

Mono<Integer> m3 = Mono.fromSupplier(() -> 1); // A lambda Supplier in which return just one value.

Mono<Integer> m4 = Mono.from(Flux.range(0, 4)); // Create a mono from the first element of a flux. You can use for mono as well.As mono can emit only one piece of data at a time, there is compatibility with asynchronous Java future objects!

Creating Flux

Flux<Integer> f1 = Flux.empty(); //Create a empty flux.

Flux<Integer> f2 = Flux.just(1, 2, 3, 4); //Create a flux with 4 elements. (1, 2, 3, 4)

Flux<Integer> f3 = Flux.range(0, 4); //Create a flux starting from 0 and increment 4x time.

Flux<Long> f4 = Flux.interval(Duration.ofMillis(500)); //Create a flux incremented based on duration.

Flux<Integer> f5 = Flux.fromIterable(Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)); //Create a flux from a iterable.

Flux<Integer> f6 = Flux.fromArray(new Integer[] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}); //Create a flux from a Array.

Flux<Integer> f7 = Flux.from(f2); //Create a flux from a Mono or another flux.There are also advanced methods like generate() and create(). However, this falls beyond this topic.

Publisher Strategies

Publishing data is not just about sending data, but also about how consumers are going to fetch and consume from it.

Cold Publisher

When a consumer consumes the data from the beginning of the stream, we refer to it as cold publisher. For instance, let’s suppose that we have a data stream of integers starting from 1 to 5. The following subscribers are going to print the same data, but with a slightly difference in the message.

Flux<Integer> stream = Flux.range(0, 5);

stream.subscribe(item -> System.out.println("First Consumer [Item " + item + "]"));

stream.subscribe(item -> System.out.println("Second Consumer [Item " + item + "]"));

Hot Publisher

This approach still follows the rule that the data will only be accessible once it has at least one subscriber. But the difference is that the data will not be replicated separately into new publishers but shared from only one publisher among all consumers. Therefore, we refer to it as hot publisher when the data is consumed from the point of receipt onward and not from the beginning.

In this case, we need to use the publish() method from the data stream to say that we are using the hot publisher approach and connect() to start it.

Flux<Integer> flux = Flux.range(1, 5);

ConnectableFlux<Integer> cflux = flux.publish();

cflux.subscribe(item -> System.out.println("First Consumer [Item " + item + "]"));

cflux.subscribe(item -> System.out.println("Second Consumer [Item " + item + "]"));

cflux.connect();

It Is possible to turn cold publishers into hot publishers by using cache(...) method.The most common use is:

| Mono<T> cache() | Turn a Mono into a hot source and cache last emitted signals for further Subscriber. |

| Mono<T> cache(Duration t) | Turn a Mono into a hot source and cache last emitted signals for further Subscriber, with an expiry timeout. |

| Mono<T> cache(Duration t, Scheduler s) | Turn a Mono into a hot source and cache last emitted signals for further Subscriber, with an expiry timeout. |

Subscriber

A Subscriber is an interface in which there is a collection of abstract methods that are designed to be invoked and respond to consuming operations. The charge of processing and fetching data to be consumed is up to the subscriber, even it is unaware of the existence of the publisher. The intermediary between the communication of publisher and subscriber is orchestrated by the Subscription Interface. In other words, subscribers start requesting for data using subscription.

public interface Subscriber<T> {

void onSubscribe(Subscription var1);

void onNext(T var1);

void onError(Throwable var1);

void onComplete();

}

public interface Subscription {

void request(long var1);

void cancel();

}

The publishers register subscribers interested in receiving data. To register a subscriber, we use one of several parameters of subscribe(…) method.

In the next example we to specify our own custom subscriber inheriting from Subscriber.

public class DemoSubscriber implements Subscriber<Integer> {

private Subscription subscription;

@Override

public void onSubscribe(Subscription subscription) {

this.subscription = subscription;

subscription.request(1);

}

@Override

public void onNext(Integer integer) {

System.out.println("On Next " + integer);

subscription.request(1);

}

@Override

public void onError(Throwable throwable) {

System.out.println("On Error " + throwable.getMessage());

}

@Override

public void onComplete() {

System.out.println("On Complete!");

}

}

The DemoSubscriber is a Integer Subscriber. In this example, we request to receive one element at a time. In order to make the Subscriber work correctly, it is almost mandatory calling request() method to fetch for more elements, otherwise the subscriber will no continue and will remain inactive. As the Subscriber can’t directly manipulate the Publisher, we use the subscription as a bridge between subscriber and publisher communication.

The order of the method calls are very simple:

onSubscribe(...)is called once a subscription occurs.onNext(...)is called N times accordingly to the requested number. We need to continue calling request to fetch elements.onError(...)is called WHEN an exception occurs from the publisher side AND NOT FROM the part of subscriber! The entire subscriber flow stops since the exceptiononComplete()is called once all data is processed.

Flux<Integer> f1 = Flux.range(1, 4).subscribe(new DemoSubscriber());

In our next articles, we will see other common ways to achieve the same result as above.

Flux<String> numericStringFlux = Flux.range(0, 5);

numericStringFlux

.doFirst(() -> {

System.out.println("Received a started signal!");

})

.doOnNext((item) -> {

System.out.println("Do On Next A " + item);

})

.doOnNext((item) -> {

System.out.println("Do On Next B " + item);

})

.doOnEach((signal) -> {

System.out.println("Do on EACH signal: " + signal);

})

.doOnComplete(() -> {

System.out.println("Received a complete signal!");

})

.doFinally((item) -> {

System.out.println("The last item was consumed " + item);

})

.subscribe(System.out::println);

Leave a comment